The ringing of the phone in the room interrupts my focus to work. They’re calling from the reception desk. It’s eleven o’clock. Wasn’t it at 12? Time seems to be a flexible term here, quite different from the one I’m used to. I put on my shoes and jacket, take my bag and quickly go out. In front of the building my driver Ginny waits for me together with Bockarie, an excellent specialist in development projects, human rights and economic development. I heard from him several times in preparation for my mission and felt somehow happy to be able to work with a man whose African experience is comparable to my European one. I see him for the first time in person. He’s a little older than me. He is thin, but bony and strong. Pleasant smile. Feeling like we’ve known each other for a long time. We hugged in greeting.

Crowded streets of Freetown

We’re heading to the office. A daily view of the streets of Freetown. Crowds, vehicle noise and horns. For me total chaos; for them a regular condition. Ke-kes, something between a motorcycle and a small car, come from all sides. All the empty space on and around the road is filled with motorcycles called Ocadas. Ke-kes and Ocadas, mostly Indian-made, replace the functionalities of urban transport. It is not unusual to see three or even four people on one motorcycle. I can’t help wondering or hiding my amazement at the traffic situation. There’s no way I’m driving these streets. There are no traffic lights. There are only several roundabouts, where no traffic rules can be applied. With a smile on his face and a palm on the horn switch, Ginny told me that the only rule is that a bigger vehicle takes priority. I assume we have a matching sense of humor. It is good that we are in the Land Cruiser with diplomatic insignia. The initial idea was that I take rent-a-car and drive around Freetown. Now, I see that there would be nothing of that idea.

Street workshop

Bockarie tells me about the work along the way. I’m trying to get used to the way he speaks and I have to be pretty concentrated to understand him. Because of me, he tries to speak clearly, but every longer conversation brings him back to the way of speaking common in his Country, as well as in a good part of Africa. Creole is a simplified version of the English language, barren of all superfluous sentence and grammatical bravados. In a way, it simultaneously reflects all the simplicity and weight of the way of life of their ancestors, at the time when it was shaped on overseas cotton plantations, and also today, in modern times. Although I can’t say that I understand much Creole, I am fascinated by the way that language has developed, accustomed, standardized and remained in everyday use. There are about sixty tribal languages spoken in Bockarie’s Country, of which he speaks four, and these languages are quite different. Without Creole, which is actually a distinct language, so different from English, although it originated from it, it would be impossible to communicate between different peoples and tribal communities. The state of language divisions in the Balkans and my unfounded polyglotism come to mind. A lot can be learned from people from this African country, only if the ears and eyes, and especially the mind, are open enough.

School children

I watch people passing by. School children are in uniforms. It is wonderful to see them walking in groups. In Sierra Leone, there are women’s, men’s and mixed, public and private schools. Primary education lasts only six years. Secondary education is not compulsory. At every step, something is sold: food, fruit, everyday trifles. The weight is mostly carried on the heads, as our ancestors did in the villages. Hustle and bustle on all sides. Along the streets are small shops and workshops. It can be assumed that people live, work and sell something at the same place. For us Europeans, it’s survival, and for them, it’s a common everyday life. It occurs to me that this country is, in a way, the complete opposite of the developed Scandinavian ones, such as Iceland, where people for generations had to use all their time and energy to survive. Nature was not kind to them. They had been acquiring and passing on the knowledge of how to survive in a harsh environment. On the other hand, in many parts of Africa, people did not have to work so hard. Nature gave them what they needed: food, clothes, shelter. They did not have to constantly worry about how to warm up, feed and survive, so the material values, but also efficiency and organization, remained far less important. The development paradigm observed in this way can provide an answer to the question why countries with scarce resources have organized their societies better. Watching the real lives of people on the streets of this multimillion African City, it came to my mind that, despite globalization and technology, the gap between the developed and the underdeveloped is actually bigger today than ever.

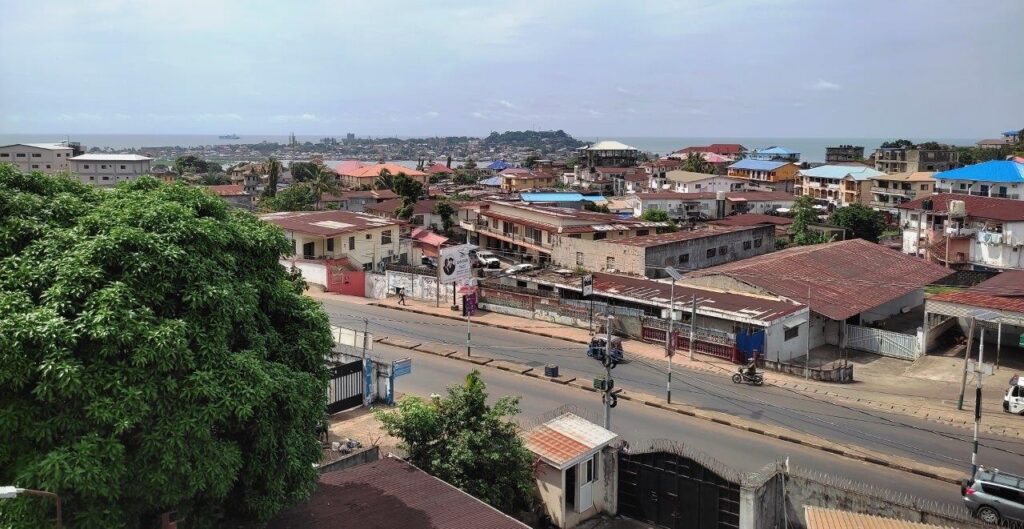

A view to West Freetown from office balcony

We come to the office located along Wilkinson Road, a wide multi-lane street, relatively close to downtown. The rather large building is surrounded by walls and barbed wire form all sides. The guards open the high steel gate for us. We enter the building next to the reception and climb up the external staircase which continues on each floor to the spacious terraces overlooking the City and the ocean. Bockarie said the office is nice. I refrain from commenting and in my mind I try to compare it with the offices of organizations and projects that I have had the opportunity to visit in some European countries. Despite the spaciousness, airiness and sun lightness, the building seems messy, dirty and neglected, almost like in a post-apocalyptic society. There is no that exterior and interior shine that I am used to and that I take for granted. While climbing to the upper floors, my view reaches neglected and dilapidated structures around the office building, with a lot of mess on the facades, roofs and earthen courtyards. From the stairs we enter the inner space. A pile of architecturally meaningless and inconspicuous rooms and corridors, and old and worn-out inventory, reminds me more of a storeroom or warehouse than an office. It is unusual how much Bockarie’s and my standard differ. I’m the one who will have to get used to it.

Surrounding of the office

We enter several rooms and Bockarie politely introduces me to the colleagues. I try to catch their names, but I can’t. I notice that there are African and Western, Muslim and Christian ones. The welcome is mostly pleasant and warm, but I still feel a kind of reserve. Well, of course, haven’t I tried to keep my distance from some Westerners who came to work in my country on many occasions, doubting their motives and good and sincere intentions? I wonder what goes through their heads: another European who came to sell us a story and take easy per diems. I was almost ashamed to have thought similarly so many times. Sometimes justified, mostly unjustified. We walk through a tangle of rooms and hallways to the other side of the building and climb another floor, then enter a secluded office in the corner of the southeast side of the building. It has been given to Bockarie for temporary use and he will soon have to look for another space to work. We sit at the same table and unfold the laptops. I try to connect to the power outlet, but the socket does not fit my European plug. Another legacy of British colonial influence. I hope the battery lasts. Officially, my first working day in Africa, in the Free City of the Lion Mountain, begins.

Great piece, Misel!

The most important is that the main character likes it. Thanks, bro!